Household debt is defined as the amount of money that all adults in the household owe financial institutions. It includes consumer debt and mortgage loans. With consumers constantly buying items on credit, it seems as though the world is starting to get into a huge consumer debt.

In Australia, Australian households have more debt compared to the size of the country’s economy than in any other world. As of the third quarter of 2015, it is now the world’s most indebted household sector relative to GDP. It has around $2 trillion in unconsolidated household debt relative to $1.6 trillion in GDP.

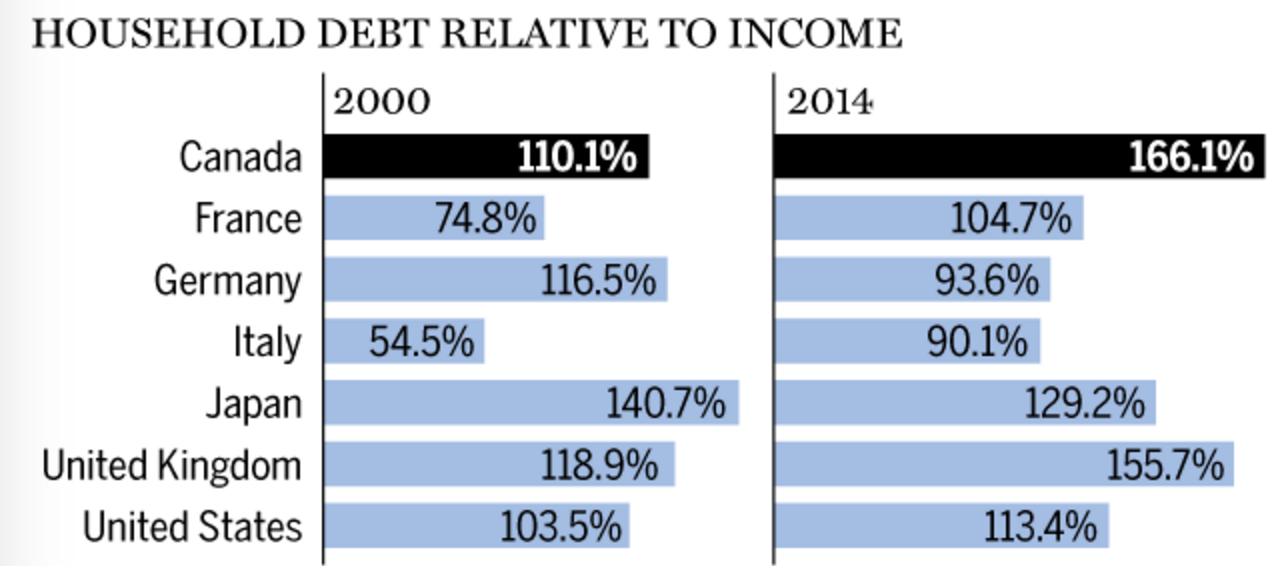

In Canada, reports showed that Canadians are ending 2015 with record-high debt and mid-2016, household debt is still growing. The Bank of Canada has expressed concerns about the elevated levels of household debt, which pose a potential risk to Canada’s financial stability in the event of a sharp economic downturn.

In Asia, China’s total debt is more than double of its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2015, and industry experts have expressed concerns that the debt linkages between the state and industry could be fatal. The country’s debt has increased to almost 250% of its GDP due to use of cheap credit to stimulate slowing growth, and releasing a massive debt-fuelled spending binge by consumers.

In Japan, it looks like the country is heading for a full-blown solvency crisis as the country runs out of local investors and may be forced to inflate away its debt in a desperate end-game. The Japanese economy is trapped in a vicious cycle of deflation and stagnation where escaping from this requires bold attempts on both monetary and fiscal fronts.

“We buy things to make us happy. And we succeed for only a short period of time. New things are exciting to us at first, but then we adapt to them.”

Consumerism is good to a certain extent as it helps in stimulating growth in the country. However, consumerism becomes excessive when it extends beyond what is needed. When we start consuming excessively beyond our income level, boundaries are removed.

Although cheap and easy credit allows us to obtain money to purchase more items. Does possessing more material goods result in increase in happiness?

A study shown by Dr. Thomas Gilovich, a psychology professor at Cornell University who has been studying the question of money and happiness for two decades, says that it might not necessarily be so. According to him, “We buy things to make us happy, and we succeed. But only for a short period of time. New things are exciting to us at first, but then we adapt to them.”

“Buying more might cause unhappiness”

This refutes the basic assumption that we’ve been holding for ages. For example – when we spend money on a physical item – as opposed to an experience, the same physical item lasts longer and supposedly makes us happier for a longer period of time as compared to a one-off experience like a concert or vacation.

In fact, buying more items might be the cause of our unhappiness. Gilovich suggests that instead of buying the latest iPhone or the latest BMW, you’ll get more happiness spending money on experiences like going to art exhibits, doing outdoor activities, learning a new skill, or traveling.

One study conducted by Gilovich showed that if people have an experience they say negatively impacted their happiness, once they have the chance to talk about it, their assessment of that experience goes up.

He attributes this to the fact that something that might have been stressful or scary in the past can become a funny story to tell at a party or be looked back on as an invaluable character-building experience.

Sharing experiences can also help us connect with others more than sharing our thoughts about our material belongings. For instance, you’re more likely to feel a connection with someone who has also taken a trip to Bali than someone who also just bought a 4K TV.

Furthermore, when we buy material goods and items, new items are exciting to us at the beginning. But over time we start to adapt to them and a vicious cycle of buying goods and items in a bid to maintain that feeling of happiness occurs.

Gilovich’s research has huge implications for individuals who want to maximize their happiness return on their financial ‘investments’, for employers who want to have a happier workforce, and policy-makers who want to have happy citizens.

If we are to take this research to heart, it means that we should not only have a shift in how individuals spend their discretionary income, but also place an emphasis on employers giving paid vacation and governments taking care of recreational spaces.

In other words, before you start spending credit on those shoes or gadget, think to yourself, do I really need this? If the answer is yes, then think of ways where you won’t need to spend money or borrow credit to get that item. Because ultimately, with the technology that’s available to us and how connected we are, we can find access to what we need before having to spend money we don’t have and create debt we may not be able to pay off.

“Happiness is not in the mere possession of money; it lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort.”

— Franklin D. Roosevelt

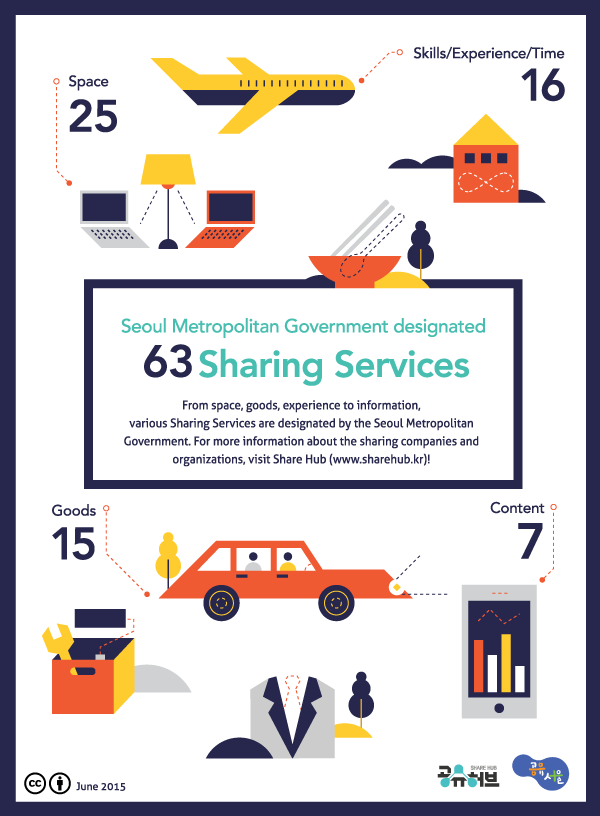

Their Sharing City Initiative defines itself by stating its overall vision as a “

Their Sharing City Initiative defines itself by stating its overall vision as a “